The Canoe Is the People

Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific

Wind

A wayfinder can know the wind direction by how it feels on his face. On the vaka, he sits where the wind hits his face directly and where he can see the ocean and horizon GLOSSARY horizon - the line where the earth and sky seem to meet ahead. Sometimes, he also watches the movement of feathers or pieces of bark GLOSSARY bark - skin of a tree attached to the sail or ropes. He can sense a change in wind direction by how the vaka feels on the waves.

The wayfinder relates the wind direction to the star positions. However, because the direction that the wind often changes, one can check to see if the position of the wind has changed by looking at the stars that the wind lines up with.

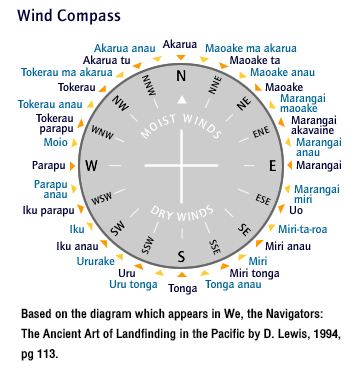

Europeans heard Pacific voyagers talking about the names of various positions around the horizon, and made drawings of the named positions around a circle. Europeans then began to call call their circle of wind positions a “wind compass.” In 1876, missionary William Wyatt Gill described the Cook Islands wind compass, which divided the horizon into 32 points. The winds were taught by using a gourd with holes in it.

“At the edge of the horizon are a series of holes, some large and some small, through which Raka, the god of winds, and his children love to blow …”

From Lewis, D. (1994).

“... for two hours, he stood there ... and he named each wind. He pointed the direction ... whether it was a cold wind, warm wind ... and when he would expect them at different times of the year.”

From David Lewis in Bader, H. and McCurdy, P., eds (1999).

In additions to the one the great Taumako wayfinder Koloso Kaveia described, there are also descriptions of wind compasses (divided into different numbers of points) from other islands, like the Carolines, Fiji, Tonga, Tokelau, and Tahiti.